A CiviCRM extension to generate – and pay out – Revenue Sharing Language plans

CiviCRM is regular used to received payments in – donations, ticket sales or membership fees – but what about automating payments out?

CiviSplit is a set of three new beta extensions to let CiviCRM admins automate paying income out to multiple parties based on a set of pre-defined rules. It could split the income from a fundraising campaign between multiple charities; or share ticket sales for an event between a band and an NGO after the organiser’s costs are deducted; or even automate the payout of dividends within a worker cooperative after expenses.

The work is being done by Matthew Wire of MJW Consulting, with support from Rich Lott of Artful Robot, and has been funded by Grant for the Web as part of a broader project looking at how to fund and support independent film online (my personal passion on the web since 1999).

The heart of CiviSplit

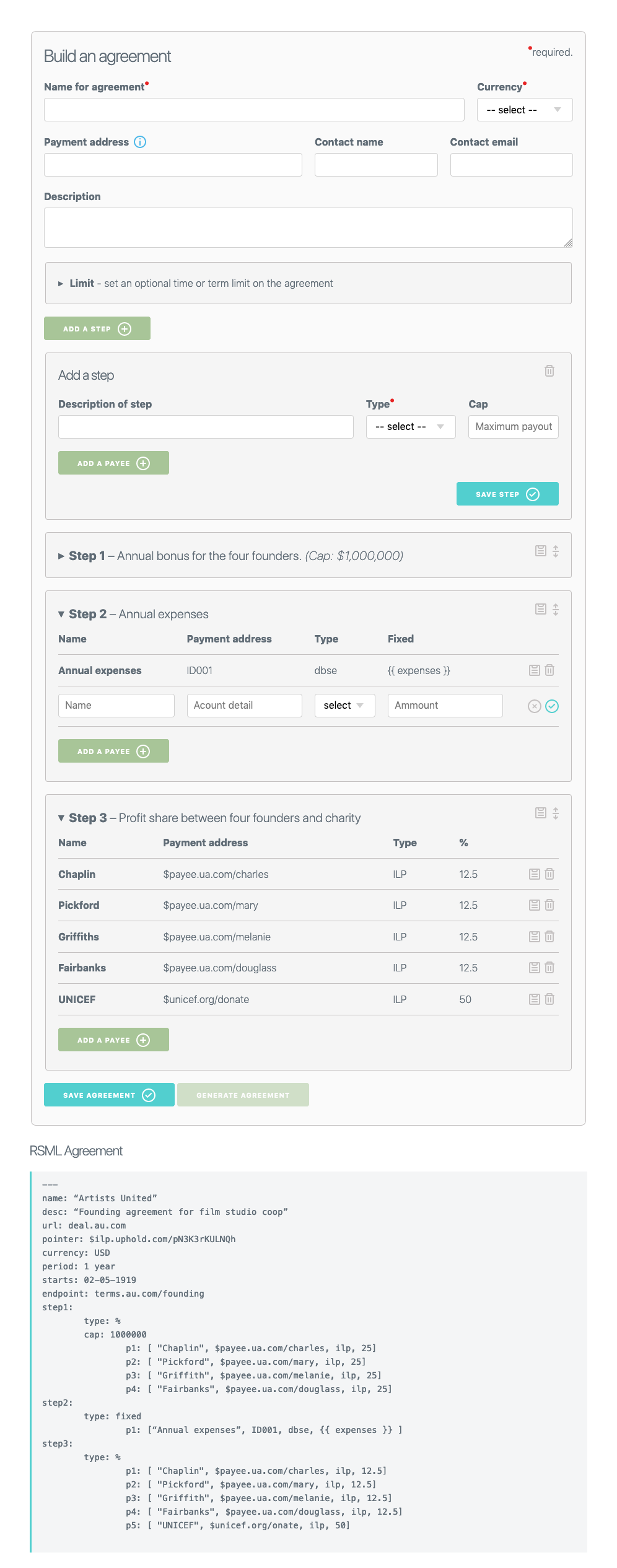

CiviSplit components will first let admins create a revenue sharing plan, then save this in a form that can’t be changed later once income arrives, then periodically check the balance of an account, and pay out what’s in there according to the plan. To achieve this there’s a few new concepts:

- We’ve created a YAML based syntax called Revenue-sharing Langauge (RSL), to describe CiviSplit agreements in a human-readable form; that can also be the basis of payout calculatations. This is how we can ensure that a payout plan that’s agreed on is the same that’s paid-out in the futture by CiviCRM. As well as feedback from Matthew and Rich, am grateful for the input of Aidan Saunders, lawyers Silvia Schmidt and Andrew Katz, and comunity-ownership expert Dave Boyle in preparing this.

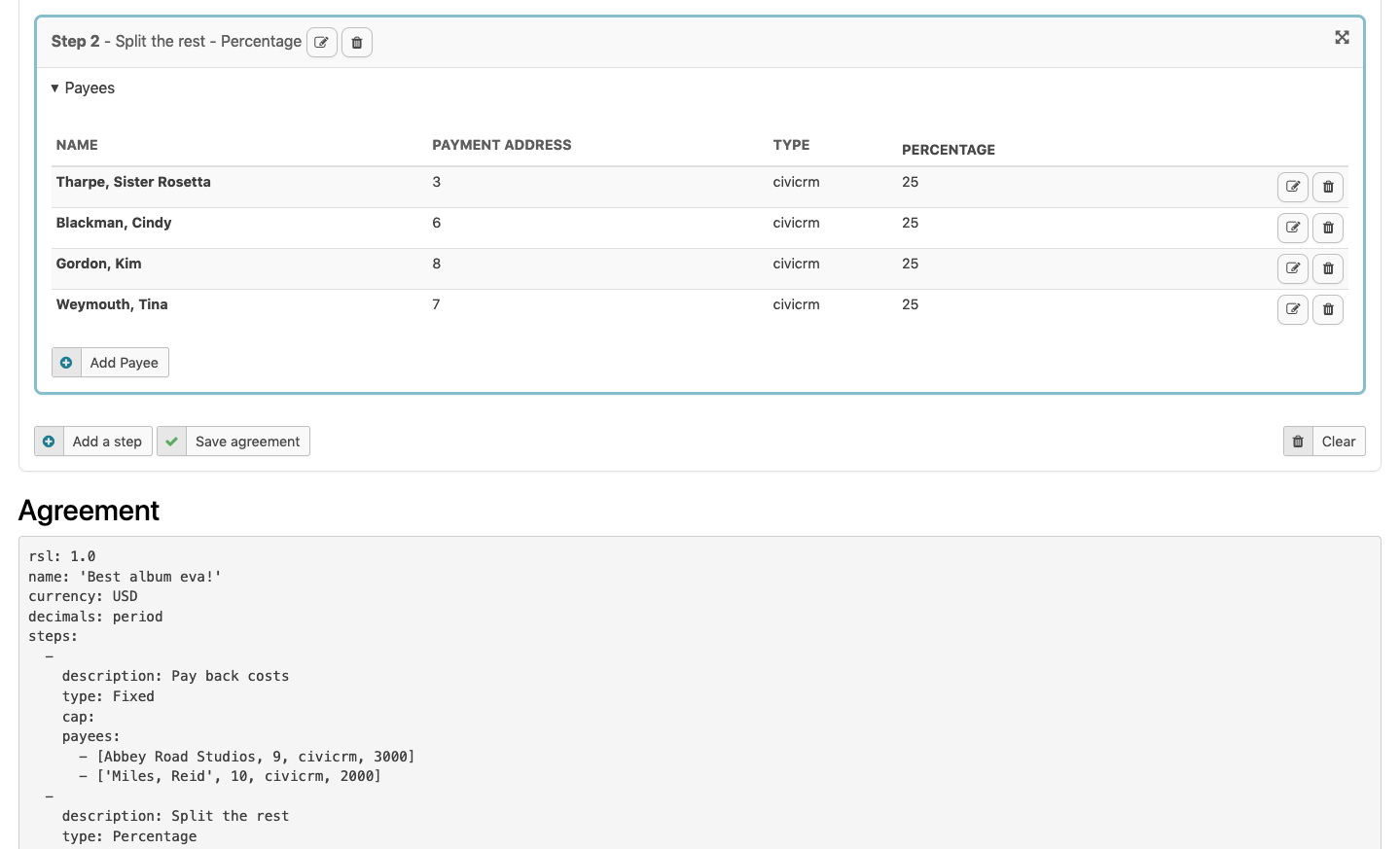

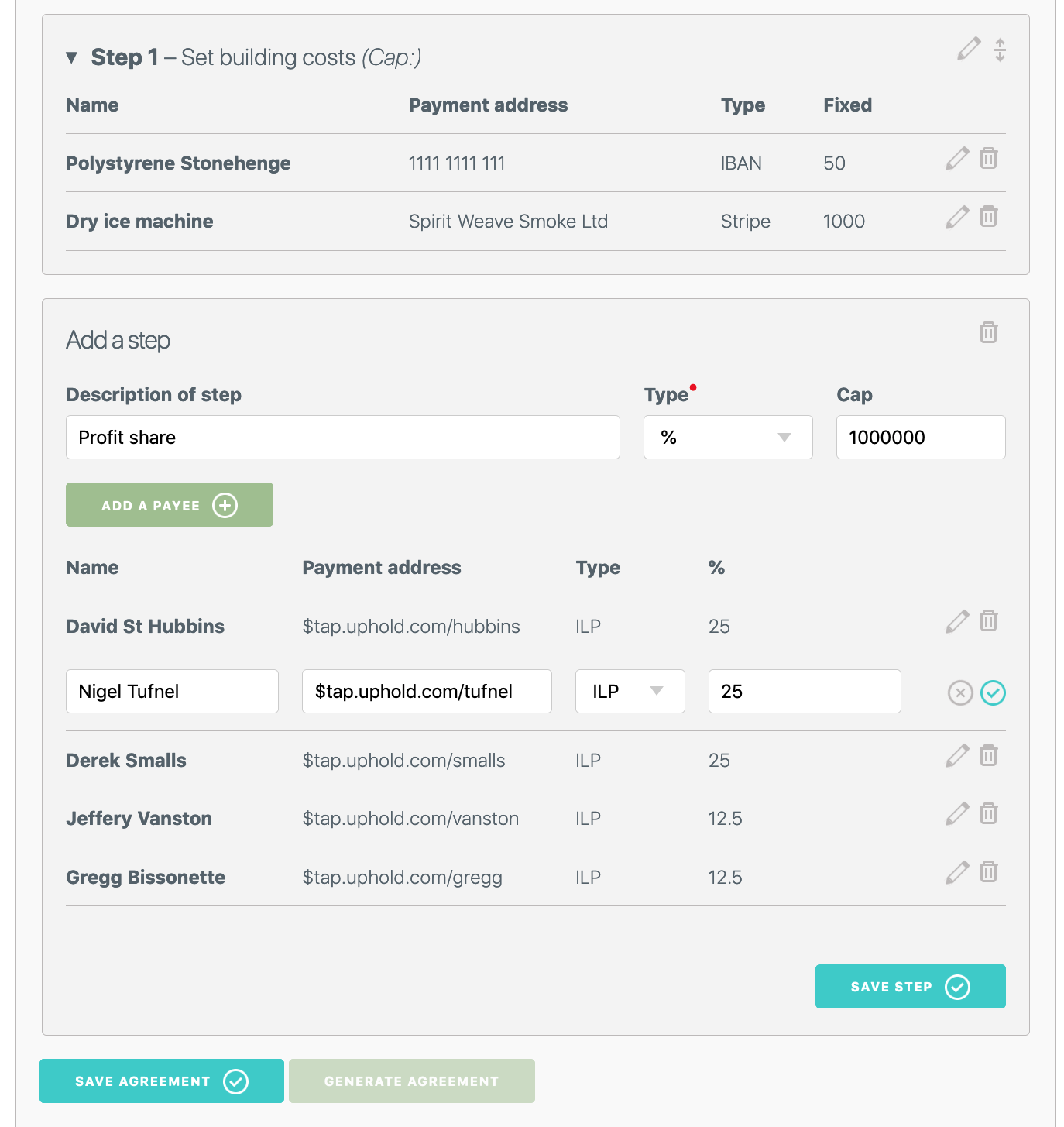

- These RSL agreements are built in CiviSplit using a drag-and-drop builder called Waterfall (a term used in the film world to determine the order people get paid). This (right) has been implemented as a standalone script so it could work with other systems – and has been built first in a framework-free native-JS by Mark Boas and then with Svelte JS by Rich Lott.

- We register negative payments on a Civi contact record’s contribution screen to denote payments to someone, rather than from someone.

- We’re using a third party digital wallet system (Uphold) to create a unique collecting ‘account’ for every CiviSplit agreement, so that monies received are ring-fenced before being split out. A new Uphold processor will manage this, and make payouts to any IBAN bank account number.

How will this all work?

- Create a payout plan: After setting up an online wallet address in their settings, users should be able to create a new CiviSplit agreement. Each step in an agreement executes sequentially with all payees at each step paid pari passu (at the same time until all are paid). So, for instance, a charity fundraising event may first want to pay back expenses to three people who are out of pocket; then they will split the income 50-50 with the promoter until the promoter has earned a pre-agreed $500 fee; and then they will take 100% of the income. This would be built by the drag-and-drop builder, creating some RSL that looks something like this:

---

name: “Fundraising event share”

currency: USD

steps:

-

type: fixed

payee:

- [ "Venue hire balance", 1234 5678, IBAN, 250]

- [ "Catering company", 1234 5678, IBAN, 150]

- [ "The DJ", name@example.com, paypal, 200]

-

type: percent

cap: 1000

- [ "Charity", 1234 5678, IBAN, 50]

- [ "Promoter", 1234 5678, IBAN, 50]

-

type: percent

payee:

- [ "Charity", 1234 5678, IBAN, 100]- Save and generate a Plan. After adjusting the agreement to ensure everyone is happy with it, the CiviCRM admin ‘generates’ it, which makes it uneditable, and creates a wallet address for the agrement, which is then saved in the RSL. Finally a cryptographic hash of the agreement is made, which will change if anyone tried to alter the agreement. A copy of the plan can then be saved as a PDF, and revisited online at a URL based on the hash. This adds some means of protection – future payouts can be checked they are still being applied to the same RSL plan, and hashes can be compared to ensure they mayvch and no changes or errors have been made.

- Use a scheduled job to trigger payouts. At regular intervals defined by a Civi Scheduled job, the wallet will be checked for a balance, and provided it’s greater than the minimum payout amount (currently €10/£10/$10) it will be split out between the payees as defined in the agreement. The next time it’s triggered payments will pick up where they left off. Pending and unresolved payouts will be held until resolved. Payouts will be trackable as entities so reports and notifications can be made to recipients of their income.

How could this potentially be used?

- Collective fundraising. Tythe.org is a fundraising protal for nine small charities. The founders recognised that many small charities spend a lot of money and energy on fundraising; while many people who want to donate struggle to choose between multiple causes. Tythe simplified the process by selecting 9 charities, and donors pay a standing monthly payment and can choose how they want their payment split. CiviSplit could make it easier to create and automate these kind of groupings of related campaigns and causes, while deducting costs before the split (ie hosting, marketing or an accountant).

- Peer-to-peer fundraising When Northbridge Digital built a large Civi/Drupal site to manage a large sponsored walk; donors could choose which charities from a select group they wanted their money to go to. This was calculated at the end by adding up the different fields users had entered; this approach could automate that.

- Cooperatives and ‘informal cooperations’. CiviCRM is already used by a number of cooperatives; some of whom track dividends to workers/users in the app. An automated payout processor could also accomodate other less formal cooperations. For instance where three Civi agencies share the cost of building an extension, then run a fundraiser to continue its development (or operate a ‘donate here’ button after launch). Make it Happens could be tied to specific CiviSplit plans so donors can see exactly how their money will be spent, and track those payouts.

- Independent creatives. Independent creators of films, art, events, books or music – like many open source developers are driven by a passion or itch, more than the (highly unlikely) goal of getting rich. For many, managing the finances is a burden; at the same time for collaborations like film productions or recording an album there can be a mix of debts, deferred fees and promises to pay someone back, which especially matter in the event a project earns something. The indie film world is littered with stories of people who worked for free on the promise of a deferred fee or profit share in the event of success, only to see nothing – and these stories inspire some of the original motivation here. But we also know, from LiveAid and Peter Pan/Great Ormond Street Hospital to Warchild and Comic Relief/Fantastic Beasts there’s long been very successful collaborations between the creative and charitable worlds, so perhaps this could support some new ones.

Shifts to automation in many areas of technology are full of problems, and it’s important to stress that we’re not proposing charities ditch their accountants for an experimental CiviCRM extension just yet. At the moment the wallet address created by the agreement will only receive one type of income stream – micropayments using Web Monetization, which is a new protocol streaming money from web users to websites as they browse the web, designed to improve how news and media is supported online. It will not be until next year that normal one-off and recurring card payments to wallets from non-Uphold users should be available. But these tiny payouts – a few cents or pennies from lots of people regularly – is where automation saves time and seems a safe place to experiment.