Introducing Revenue Sharing Language – a Web Monetization answer to Hollywood accounting?

Scarlett Johansson’s recent contract dispute with Disney and their thunderbolt response that she had ‘callous disregard for the suffering of the pandemic’ showed Hollywood’s power players on the brink of civil war. The LA Times suggested the fight, and Disney’s diss at Marvel’s biggest female star, was really about a bigger question: “how should stars and filmmakers be paid for movies and TV shows now that the business model is shifting quickly from one based on box office and television ratings to one reliant on online subscriptions?”. It’s easy to calculate how to earn a cut of ticket or DVD sales for a film, but what about ‘all you can eat’ flat-fee subscription video services where some people watch one film a month – and others dozens a week?

To those in the Web Monetization (WM) community, the answer is maybe simple – they could get a share of every second that a subscriber is watching for. A Coil.com plugin in the subscriber’s browser, streams $0.36/hour to the website’s Payment Pointer for the first 12 hours each month, and tapers off after that. Amazon Prime also pays filmmakers per seconds viewed, tho at a much lower and well-guarded, rate. Problem solved? Web Monetization could turn subscription income into profit-share for every second viewed of any film that works for all but the biggest platform users.

However, a Payment Pointer only points to one wallet, in reality, the premiere of Scarlet Widow 2: Implausible Resurrection on Cinnamon in 2024 would want to pay out to many different wallets: the website, the production company, Marvel and all the stars guaranteed a share of the profits.

Sharing Web Monetization payouts precisely

Probabilistic Revenue Sharing is WM’s answer to this, which works by letting the hosting website list a number of payment pointers and a value for what percent of visits each pointer should be the receiving wallet for. If it’s 50% Disney and 50% Scarlett; every other view of the page would load each payment pointer, so the amount paid out should be largely equal after a few hundred views. But for videos with a dozen or more payees, or feature films with 120 minutes per view and only a few dozen views, it’s easy to imagine how quickly probabilistic payouts become less than precise.

In our Grant for the Web project, MOVA we’re taking another approach – with a CiviCRM tool to log into the wallet behind a payment pointer, check the balance, then distribute payments to multiple parties depending on a set of pre-agreed rules. This opens up the possibility of more creative repayment structures that take account other obligations – like paying back the drone hire company for your shoot and the cinematographer’s deferred fee, then the loan from your rich great-aunt, before splitting what’s left fairly between the production cast and crew. And how much easier might it be to get that rich great-aunt’s loan if she doesn’t have to depend on her nephew’s accounting skills to get repaid?

Once we started exploring the tool we hit a question: how can payees be sure that they are receiving the right amount? Even ignoring fraud, how could the system check that payouts are accurate? Could there be a machine- and human- readable version of the revenue split that could be hashed/printed out and also used as the basis for payouts? This idea of a human and machine readable agreement is sometimes known as a Ricardian contract. This would have the benefit of letting us develop something that other systems could read and produce; using, like Web Monetization, Interledger and Payment Pointers, a decentralised approach. Researching the space it soon appeared that while there is a sophisticated machine readable rights language – Open Digital Rights Language; and there are multiple systems for writing up contracts with machine readable syntax, including Smart Contract templates, and the Accord Project, we’ve not found a syntax for revenue sharing agreements.

Introducing RSL

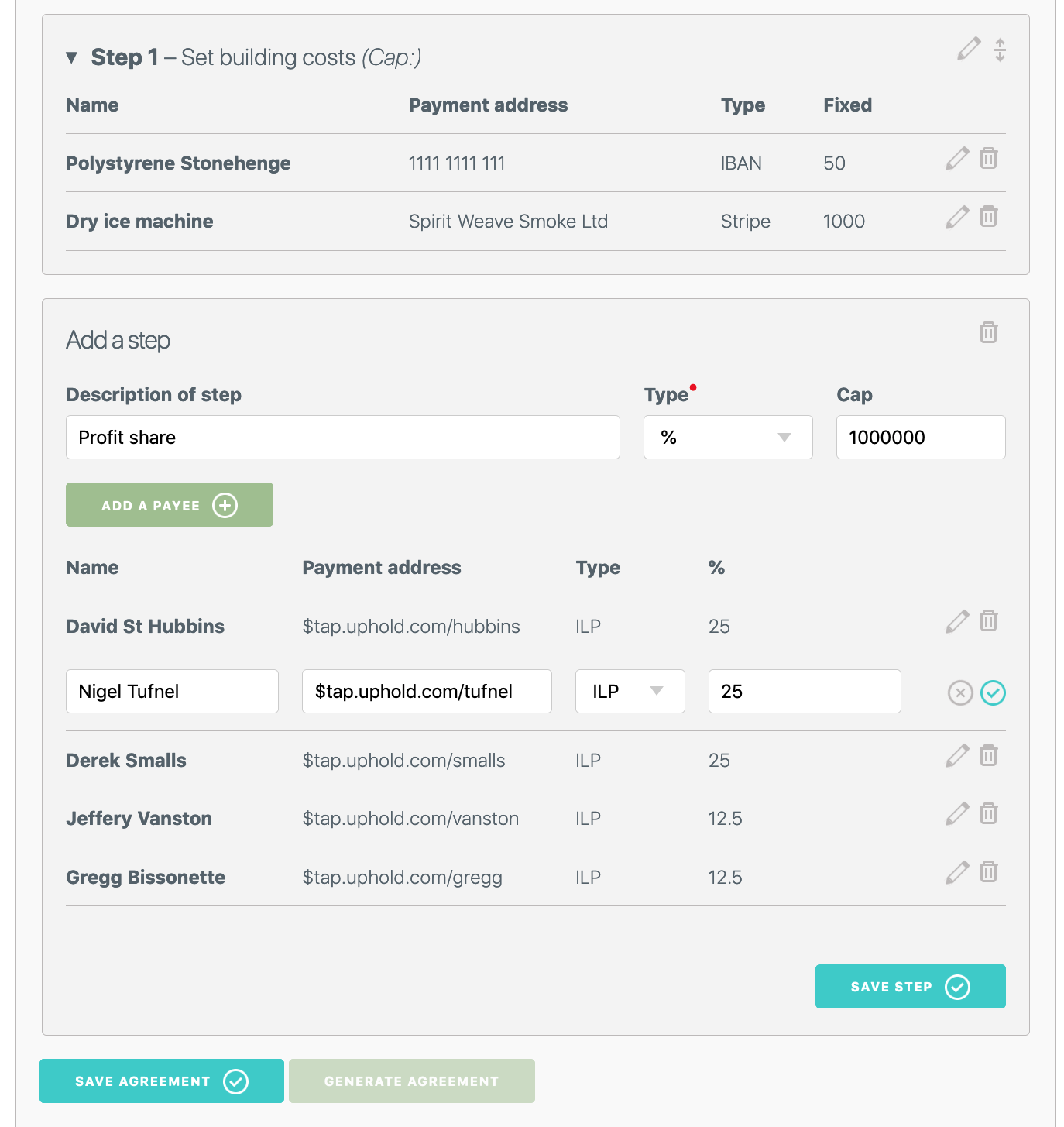

Revenue-Sharing Language (github.com/openvideotech/rsl) is a proposed YAML-based vocabulary and syntax to describe how revenues received at a wallet, pointer or account should be distributed. It uses YAML to make it easier for non-developers to read, with agreements structured as a series of steps. MOVA’s revenue-sharing-agreement builder will output this syntax, which will then be used as the basis for payment distributions on an ongoing basis by the CiviCRM extension we’re building.

Each step in an RSL agreement pays out either fixed amounts or a percentage split – before flowing onto the next step. Steps could have one payee or hundreds; and each payee can be identified with an ILP payment pointer (or a bank account, wallet address or other payee address). RSL isn’t intended to generate or implement the agreements – that’s the next task in our project – but rather to provide an open serialisable basis for structuring them.

In the spec for RSL – which we are inviting comments and feedback on – we have six examples of different kinds of payout structures. For instance, the below YAML maps a traditional publishing advance deal where a writer gets 25% of royalties, of which 10% goes to their agent, after they’ve repaid their advance to the publisher in the first step.

---

name: "Best of times, Worst of times"

description: "Book deal for the new novel by Charlene Dickens"

pointer: ilp.uphold.com/191320x91

currency: EUR

steps:

-

type: fixed

payee:

- ["PRNG House", $ilp.example.com/prng, ilp, 40000]

-

type: percent

payee:

- ["Charlene Dickens", 12345678/12-34-56, uk-ac, 22.5 ]

- ["Internet Aritsts Management", payment@example.com, paypal, 2.5]

- ["PRNG House", $ilp.example.com, ilp, dbse, 75 ]

Of course these agreements could get very complex and RSL probably wouldn’t be able to accommodate sophisticated, high-end royalty agreements. Gerard Butler’s contract payout dispute over Olympus has Fallen, for example, appeared a few days after Johansson’s and “entitled him to 10% of net profits, plus 6% of domestic adjusted gross receipts above $70 million and 12% of foreign adjusted gross receipts above $35 million… [plus] 5% of net profits” to his production company and “certain bonuses for hitting box office thresholds”.

Hollywood accounting

Once we look at LaLa Land salaries and bonuses it may feel a little abstract – a company making billions in profits on one side and a star earning more per movie than any YouTube influencer will probably make in their lifetime. But Butler and Johansson are the tip of the iceberg of ‘Hollywood accounting’ long famed for finding creative ways to ensure that, for instance, Return of the Jedi, Spiderman, Batman and Harry Potter: Order of the Phoenix are all technically loss-making —despite huge commercial success— so never have to pay out profit shares to their cast and crew.

And many contract payment disputes outside of Hollywood involve regular creators who’ve hit it big. Consider Nomcebo Zikode, the singer of last year’s lockdown hit Jerusalema (440 million views on youTube for the original so far, and countless views for the tribute dances) and who claims to still have not been paid one cent because of a contract dispute with DJ Master KG who she made it with. KG counters that the issue is Zikode wanting a 70-30 split, not the 50-50 he claims they agreed. The lack of a documented agreement Zikode and KG can reference leaves it potentially down to whoever can afford the better lawyer. This is a sad outcome for a song that gave cheer to many millions of people during lockdown both listening and dancing to it.

The TikTok Dance Strike – credit… and payment?

Dance mashups brings up another question – that of unpaid and often uncredited choreographers of viral hits. For example Fenomenos do Semba – the Angolan dancers whose original eating-while-dancing choreography for Jerusalema doubtless helped the hit, and made it easy for others to copy the dance and make the countless remix videos.

This subject got attention this summer after a Jimmy Fallon segment where Addison Rae danced viral TikTok dances without crediting the choreographers. While Mya Johnson, the 15-year-old whose choreography to Cardi B’s Up was performed on the show was gracious, this lack of due props drove this summer’s Black TikTok Dance strike.

Attribution will doubtless improve (the Tonight Show and Rae both had to respond to the backlash) – but what if a hit songs’ revenues could be shared with choreographers whose work goes viral?

In RSL we have proposed a ‘Variable Syntax’ which would allow making agreements with people who aren’t known at the time the agreement is made. It was designed so that a filmmaker could share their Monetization income with a website or influencer who hosts their film, but it could maybe also work with future choreographers whose routines help a song go viral. Given the complexity of making that work accurately and securely, we aren’t currebuilding out Variable Syntax during this round of work within MOVA, but it’s included in RSL as it seems interesting – and as an open language maybe others will try to implement it.

So I’m very pleased to share RSL for feedback, criticism and review. It’s been created with much helpful input from readers including Mark Boas, Laurian Gridinoc, Rich Lott, Aidan Saunders, Silvia Schmidt and Kevin Wittek — many thanks to them – and also Adam Davies, for helping inspire this tool, following the years of manually calculating royalty payouts for our Film Finance Handbook.