I hope you forgive the clickbait headline, reader, as our project isn’t a video Wikipedia. But the subject is a good thought experiment to introduce some of the motivations around ‘open video’, and explain some of the backstory to our project MOVA (Monetizing Open Video Assets), which has just started this week.

‘Video Wikipedia’ is a long-discussed concept that slams fast and hard into technical, social and funding questions: what is the interface for collaborative and transparent video editing that’s as easy to use as a Wiki? How would you host and serve that much video? How could you moderate for quality, accuracy and legality of media? How would such a project be funded? What might motivate videomakers to contribute?

While Web Monetization may offer answers to the funding question, the scale of the other challenges, not to mention the carbon footprint of video online versus text, triggers an immediate question – why does the planet need a video wikipedia? Simply literacy: for the 773 million adults around the world who cannot read, two-thirds of whom are women, Wikipedia is useless – and that’s before considering many people’s low reading skills or learning styles. According to Wikimedia Sweden, a quarter of Wikipedia users prefer or need text in a spoken form. For as long as Wikipedia can’t serve these people’s needs, YouTube will – yet without an editorial process to ensure quality, accuracy or ‘neutral point of view’.

Pratik Shetty, the co-founder of the most recent attempt to solve the problem, VideoWiki, was inspired after seeing the presence of mosquitoes near his building and warning the building’s security guard they could cause dengue fever. The guard reassured him that he could treat dengue by himself without visiting a doctor, showing a YouTube video that listed five at-home remedies. When Pratik advised him to get his medical advice from Wikipedia not YouTube, the guard explained he cannot read.

Shetty and Hassan Amin’s VideoWiki isn’t the first attempt to solve the problem; the subject has a long history – WikiTV dates back to 2005, and in 2008 open source collaborative video editor Kaltura added a MediaWiki extension and announced a partnership with Wikimedia to bring rich media to pages. But it struggled to take off, and the VideoWiki lists under 150 articles articles made into rich, editable media. As Wikipedia itself says, the incorporation of video into wikipedia is still at ‘a very early stage’ and although there are 135,000 videos listed on WikiMedia Commons many seem likely to have been generated by the Open Access Media Importer project, a bot which imports public access scientific video from PubMed Central.

As I left the FOSDEM Videowiki session in Brussels in February 2020, I found myself wondering why there wasn’t more open video on Wikipedia. Part of the answer is simple: money. It’s far cheaper to write a Wikipedia entry or share a photo than produce a professional-quality video. Furthermore, Wikimedia’s Creative Commons licensing doesn’t allow for non-commercial, so filmmakers wanting to still sell their film to Netflix can’t also share parts of it to Wikipedia without allowing someone else to then sell a version of it to Amazon.

As it happened I’d just that day filmed an interview with the co-founder and former ‘Benevolent Dictator’ of CiviCRM, Donald Lobo for an ongoing, somewhat neglected project of mine, making Creative Commons SA video around the CiviCRM community: screen.is/civicrm/. It had struck me that Lobo’s interview would be interesting to people outside of CiviCRM as well: he was employee number five at Yahoo; and thru his Chintu Gudiya Foundation is involved in a range of transformational open source development projects in India. I’d been lucky to get the interview at short notice, so what gave me the right to exclusively own a 30 minute interivew, for the two minutes that might make its way into a final film of mine?

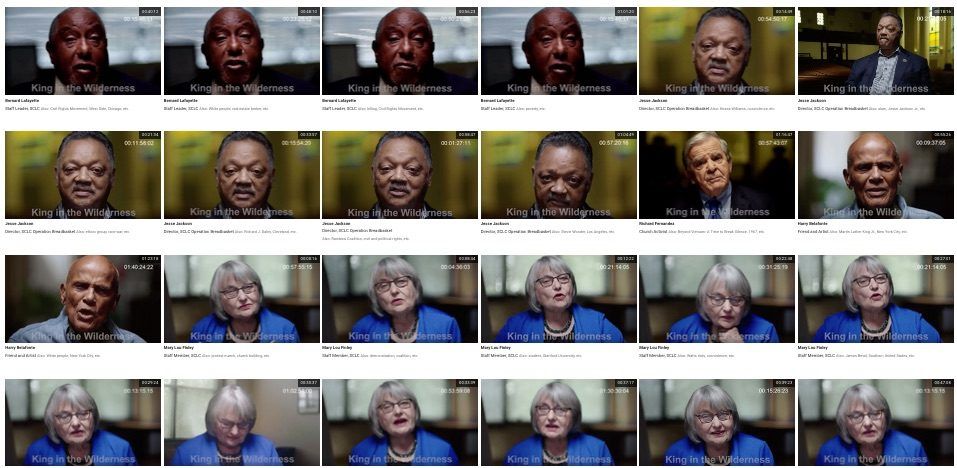

At another FOSDEM session on Wikibase, I learned of JSTOR’s Interview Archive for Peter Kunhardt’s HBO film about Martin Luther King’s last three years: King in the Wilderness (pictured top). The film is a historical document, but so are the uncut testimonies of each of the interviewees. JSTOR labs created a searchable database of each interview for the documentary, complete with transcripts, tagging, metadata and background information from Wikipedia. https://www.youtube.com/embed/MutfvpFS6G0

JSTOR’s Ron Snyder talking thru the project explained how ‘some of the best stuff ended up on the cutting room floor’. This is something I’ve mentioned before here and is well known to filmmakers but not necessarily viewers — just how much footage is never shared in order to make a tight and snappy final cut. Peter Kunhardt’s Film Foundation, has since put the interview archives of more documentaries online but not with the JSTOR interface and it’s not caught on further.

These three takeaways from my weekend in Brussels at FOSDEM were whirring around my mind as I got on the train back to London:

- Wikimedia doesn’t have enough good quality Creative Commons BY/SA licensed video;

- Documentary filmmakers effectively bin millions of hours of footage that never makes their final cut each year;

- For some cultural projects the full unedited video provides value and importance as a source text. If you’re lucky as a filmmaker to interview a historically or socially significant figure – is there a responsibility to share their uncut story? It also can add context at a time when the stripping of context on social media is, in the words of Charlie Warzel, creating a ‘one-dimensional space’ for culture.

After the Grant for the Web first call was announced and I started testing Web Monetization, came an ‘aha moment’. What if the potential for Web Monetization income could encourage filmmakers to open up more of their assets? More open assets could mean, eventually, better video on Wikimedia and more interesting works using those assets. Perhaps it can even share monetization between orginators and remixers, as Mark Boas has discussed with Hyperaudio.

Over two GftW application processes, the seed of an idea germinated into project MOVA, which I’m really excited to finally getting going on – with a great team and perhaps the most exciting technology – in Web Monetization – I’ve seen in 21 years thinking about filmmaking on the web. In the coming months I’ll dive deeper into what we’re building, and the surrounding questions around video rights, discovery, moderation and sustainability, but for now – hello – I’m really looking forward to this journey.